Sudan, South Sudan, Mali – are African countries already facing or risk entering catastrophic food insecurity; While the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria, Somalia, Burkina Faso, Chad, Kenya are classified as “very high concern.” A new United Nations report raises deep concerns about food insecurity in the continent.

A very recent report from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) (‘Hunger Hotspots: November 2025 to May 2026 outlook), paints a devastating picture of global acute food insecurity. Yet, the report’s geography is painfully familiar: Africa is once again disproportionately represented among the most critical crises, with nine nations flagged as imminent or very high concern.

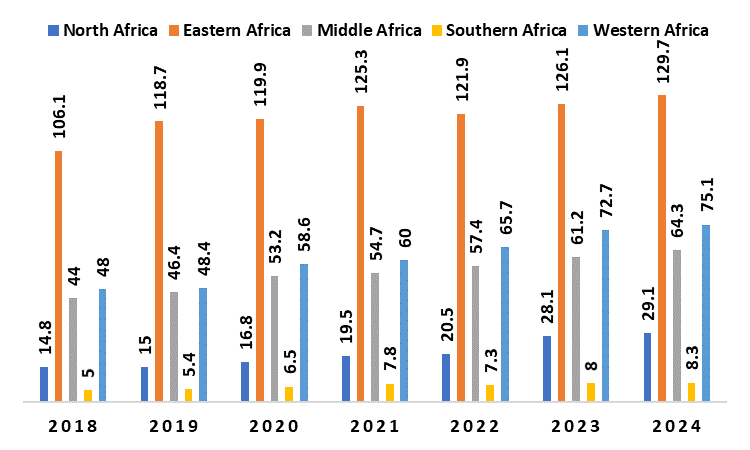

Africa, sadly, dominated the list of global 16 facing acute food insecurity and hunger with 9 regions. The number of undernourished people in Africa has increased a lot from 217.9 in 2018 to 306.5 in 2024, that is a 71% percent increment in 7 years.

African Population facing hunger (millions).

DATA SOURCE: UNICEF

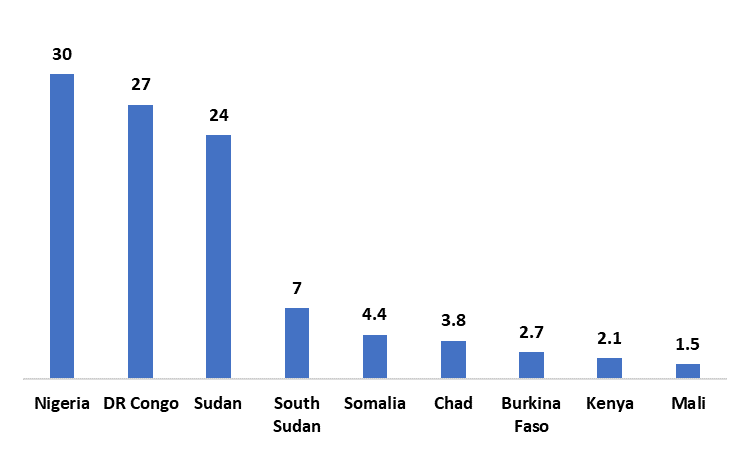

In West Africa: 30 million in Nigeria, 2.7 million in Burkina Faso, 1.5 million in Mali; North Africa: 24 million in Sudan; East Africa: 2.1 million in Kenya, 7 million in South Sudan, 4.4 million in Somalia; Central Africa: 3.8 million in Chad, and 27 million in DRC.

9 countries facing catastrophic hunger (millions)

DATA SOURCE: FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION (FAO)

Over 103 million Africans are at risk of “facing catastrophic hunger” in 2026 according to FAO.

African population facing chronic hunger in each zone (millions).

DATA SOURCE: FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION (FAO)

This is not just a collection of unfortunate incidents; it is a systemic failure where the combination of relentless conflict, a volatile climate, and crippling economic shocks is systematically destroying livelihoods and testing the resilience of African communities to their absolute limit.

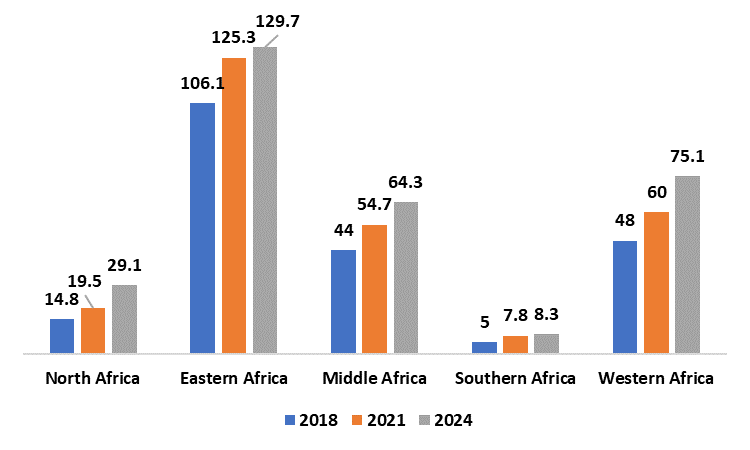

Growth of population facing chronic hunger in each zone in millions.

DATA SOURCE: FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION (FAO)

The chart above shows the growth rate of food insecurity across regions, North Africa has almost doubled with a 97% increment from 2018 to 2024. Southern Africa 66%, Western Africa 56.5%, Middle Africa 46%, and Eastern Africa 22% during the same time frame, respectively.

Conflict: The engine of catastrophe

Conflict and violence remain the primary engine of hunger in 14 of the 16 global hotspots. In Africa, this reality is most felt in Sudan and South Sudan, two nations categorised in the highest concern bracket (IPC/CH Phase 5), meaning populations face an imminent risk of catastrophic hunger or famine.

In Sudan, the internal conflict has ripped through the country’s agricultural heartlands, displacing millions and confirming pockets of famine in 2024 with projections for further expansion. It is a man-made disaster where farms are abandoned, markets are destroyed, and humanitarian aid is deliberately blocked.

To the south, South Sudan is enduring a complex crisis where political instability is compounded by the sheer destruction of its limited infrastructure. As the report notes, the economy is projected to contract by more than 30 per cent in 2025, a statistic that translates directly into skyrocketing food prices that few can afford.

Conflict used as an economic weapon

The crisis extends west into the Sahel region, where Mali, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and Chad are flagged as urgent hotspots, demonstrating how armed violence has become a mechanism for systematically eroding food systems.

Mali remains a hotspot of highest concern (IPC/CH Phase 5). Persistent conflict and extreme access constraints in northern and central regions continue to disrupt food systems. Reports indicate that armed groups, such as Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), are now using blockades to cut off economic supply lines to urban centres in the west and south, intensifying fuel shortages and driving up food prices well above the five-year average.

By August 2025, over 1.5 million people were projected to face Crisis (CH Phase 3) or worse conditions, with a small population in Ménaka at catastrophic risk.

Nigeria is categorised as “very high concern” due to pervasive insecurity, particularly in the northern states where persistent armed conflict and banditry force farmers and herders off their land, turning food producers into food dependents overnight.

Meanwhile, Burkina Faso and Chad continue to face unrelenting pressure from widespread violence and insecurity, leading to massive internal displacement and critically constraining access for humanitarian assistance.

The combined effect across the Sahel is a deepening cycle of violence, market disruption, and forced reliance on an increasingly underfunded international aid system.

Climate and economics: The dangerous cycle

While conflict provides the immediate shock, two other drivers guarantee long-term vulnerability: climate extremes and economic failure.

In East Africa, the cyclical violence of nature continues. Kenya and Somalia are predicted to face yet another below-average rainy season, threatening crops and pastures. For pastoralist communities, this means the death of livestock—their primary wealth and sustenance—forcing them to liquidate their few remaining assets just to buy a single meal.

East African countries (Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania) have the highest agricultural share of GDP in the continent with a 27.32% average across the three nations.

Conversely, in South Sudan, the climate threat manifests as catastrophic flooding. The persistence of La Niña conditions until early 2026 heightens the risk of massive floods, threatening up to 1.6 million people and destroying harvests, demonstrating that for many Africans, both too little rain and too much rain spell disaster.

This climate-induced uncertainty is amplified by a crippling global economy. High debt burdens and uneven global recovery mean that even where food is available, it is often out of reach.

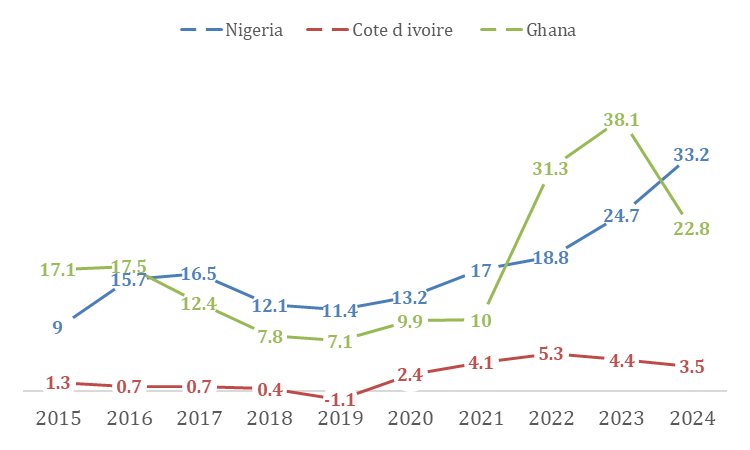

The level of food inflation in West African countries is very rapid compared to other regions indicating fast reduction in purchasing power of the households to secure food especially since after the pandemic.

Inflation in some West African Countries.

DATA SOURCE: INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND (IMF).

FAO flagged Nigeria for ten consecutive years of double-digit inflation, currently at 16% in October 2025.

For the average family, this inflation is a daily, exhausting battle: the cost of maize (their staple) in Kenya is elevated, and the price of seeds (their future) continues to rise while their currency continues to weaken.

The report states that by late October 2025, only $10.5 billion of the required $29 billion to assist those most at risk had been received.

This gap is not abstract; it forces humanitarian organisations to make impossible choices. Rations are cut. Critical nutrition and school feeding programmes are suspended, leaving millions of children, refugees, and displaced families in an extreme state of vulnerability.

Furthermore, FAO warns that lack of funding cripples efforts to protect agricultural livelihoods—the very fabric of self-sufficiency. Without anticipatory actions—getting seeds, tools, and livestock health services to communities before a crisis hits—millions of smallholder farmers lose their capacity to feed themselves.

Africa has low output per hectare of land compared to the rest of the globe. Intensification is the way forward. Africa needs to increase output per hectare by securing better seeds, fertilizers and proper irrigation structure rather than land expansion.

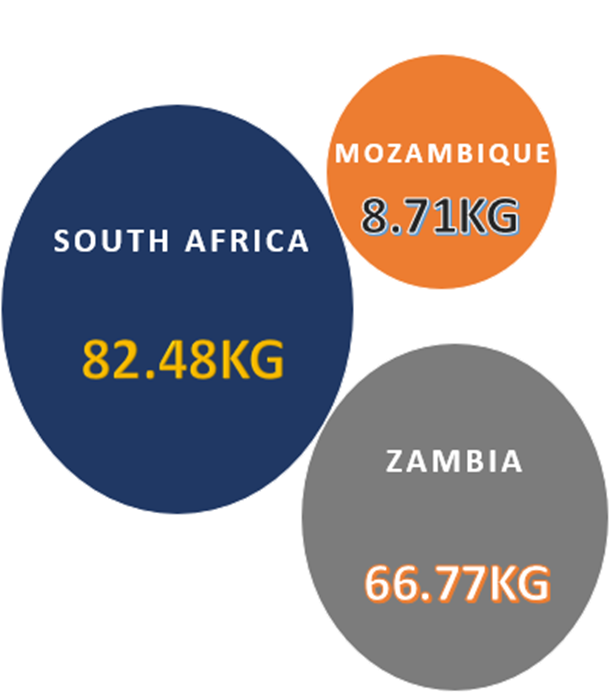

The global average fertilizer application rate is quite high, generally falling between 135 and 146 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha) of arable land. However, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) lags significantly behind, with usage rates typically less than 20 kg/ha, making it the region with the lowest usage globally.

The average for the entire African continent is higher, estimated between 34.5 and 47.7 kg/ha, but this figure is heavily influenced by high-use countries in North Africa (like Egypt) and South Africa.

High use countries like India apply approximately 193 kg/ha, while countries like the Netherlands use around 274 kg/ha, and Brazil uses an even higher 370 kg/ha, underscoring the massive difference in application intensity compared to Africa.

African leaders at the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health (AFSH) Summit held in Nairobi, Kenya, in May 2024, set a target of increasing fertilizer application to 50 kg/ha – a target very below global average.

Fertilizer use per hectare of land in some Southern African Countries.

DATA SOURCE: WORLD BANK.

Prevention is infinitely better than reaction. Investing in sustainable farming, water harvesting, and peace-building initiatives is not merely a moral duty; it is the most effective economic investment in long-term peace and stability.

The world’s early warning systems are working, but the response system—the political will and the financial resources—is failing to heed the warnings. Millions of African lives, caught between bullets, floods, and famine, depend on proactive investment.